A discussion of ‘Civility’ as an axis for exploitation and subjugation of post-colonial Senegal in Ousmane Sembène’s film ‘Black Girl’ (La Noire de…)

The French colonial possession of Senegal began in 1884 and subsequently its ‘citizens’ had to submit themselves to the French ‘code civil’, part of the French policy of assimilation. Beyond the control of the people’s wealth and its production France espoused an additional goal of transforming the African populations within its sphere into French citizens;1 to, as Brand Nubian put it in their song ‘Wake Up’, ‘…civilise the uncivilised…’2 However, this was not the empowerment of the African diaspora as proposed by the group, but as a way to perpetrate subjugation. The French Civil Code and its imposition spoke to the political, the economic, the judicial, and the rules and laws that governed them. There are also rules of propriety, that have a formality of their own; behaviours that indicate a shared and equitable humanity. A code of civility. It can be observed in Ousmane Sembène’s ‘Black Girl’ that it is the absence of ‘civility’ that leads to a cultural and political awakening in its central figure Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop).

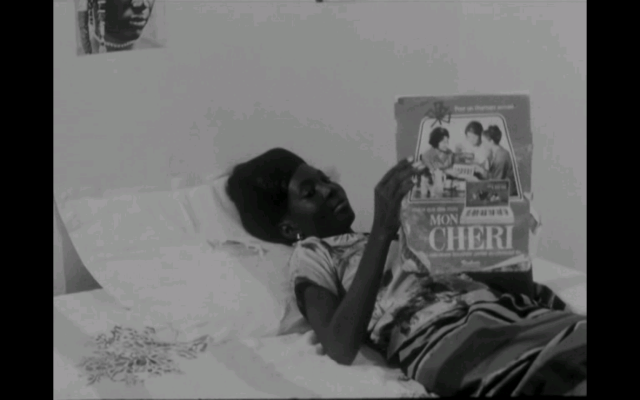

In Dakar, Diouana was contented as the nanny to the family she re-joins in Côte d’Azur. She relocates expecting a continuation of that role, and is also thrilled at the prospect of ‘…beautiful people, appealing consumer items, and adventure…’3 Dakar, along with Gorée, Rufisque and Saint-Louis, formed the ‘quatre communes’ of Senegal which were the only African territories in the French colonial period where African inhabitants (- *originaires4 -) were granted the same right as French.5 Originaires political and cultural navigation of colonialism and subsequent privileges resulted in the development of a hybridized identity – a combination of Senegalese indigene and French citizen, that construed in the imagination a sense of ‘**special status’6. Perhaps it is this chimera that informs Diouana’s naïve expectations of her life in France. She is summarily disabused of them all.

Diouana’s voluntary dispossession immediately ushers in drudgery not glamour, a ready confinement of cooking, laundry, cleaning, babysitting and immobility. On arrival at the family’s modest apartment, she is greeted by Madame (Anne-Marie Jelinek) with a perfunctory handshake, a sunless greeting for someone who the audience comes to know is a trusted caretaker of Madame’s children. This moment is bereft of ordinary civility as Diouana is offered neither a drink, food or a seat after her long transatlantic journey by sea. Instead, she is given a tour of the domicile she is expected to maintain and only shown Côte d’Azur, France, at a distance through a window.

The inhospitality of this new terrain is portended in Diouana’s landing. She is met, as she disembarks, by Monsieur (Robert Fontaine), who simply says, “You made it,” and “Let’s go.” No greetings are exchanged. In the car, only a perfunctory conversation ensues. Silence accompanies the rest of journey. This ‘citizen’ views the ‘mother country’, at a distance, through the windscreen, captive, within the enclosure of the car. This new landscape lies in stark contrast to Diouana’s remembering of life with the family in Dakar. There, her role was solely that of nanny to the children, not an assumed factotum as she is in Côte d’Azur; she is gifted cast-off dresses, slips and shoes by Madame, and she is paid. Her employer’s munificence, though, is a mask, or as Black Star put it in their song ‘Thieves in the Night’: “Not compassionate, only polite…Not good but well behaved…”7

A wooden mask is the first site of the incivility Diouana is to experience in her relationship with the couple. Bought from her brother (Ibrahima Boy) as a gift for her new employer, she presents it to Madame. She does not expect a ‘thank you’, but nor does she receive one. Rather Madame simply asks, “Is it for me?”, quickly followed by an exchange with her husband in which he makes an economic evaluation of the object, “Looks like the real thing.” The status they believe they hold is suffused with an entitlement that forestalls even polite gratitude – something that acknowledges the equality of their humanity. In the hands of the couple the symbol becomes a thing – civility is reduced to commodity. The status Diouana holds in their estimation means that she is regarded as: transactional, artless, object.

For the Black Girl propriety has no place in polite society. Body, mind and spirit are objectified through lenses of both the exotic and erotic at a luncheon where it is demanded she cook ‘African’ rice for the couple’s guests; rice that Madame and Monsieur never ate in Dakar but served to people who talk about Senegal, but not to her. One male guest does not possess the civility not to nakedly ogle her, or the restraint not to invade her personal space, as he has never kissed a black woman before. Diouana is offended and angry, but there is no reproach for the guest’s transgression. Madame minimises this bad act with a forced, perfunctory ‘apology’, following it immediately with a request for coffee for the party, including Diouana’s assailant. The ‘civil’ regard her only as uncivilised. She is not a ***gourmet8. This attitude is amplified when a guest remarks on her ability to function with such limited French, saying that she must understand it “instinctively…like an animal.”

Incivility persists with its indifferent harm as Diouana is constantly accused of being lazy. She has not been bought a uniform, yet is further chastised for not wearing appropriate attire in the commission of her work. She is only permitted trips to the market, and because the couple do not pay her regularly, she cannot go out to explore. She is offered no chaperone, something that Monsieur manages to find when he returns to Dakar towards the end of the film. The gentility gap can be measured by Madame’s remark to her husband that Diouana is “wasting away”, after first being denied food and later refusing food as a form of personal reclamation. ‘The fact that the couple perceive Diouana’s decline and yet fail to relieve her suffering is so profound an illustration of the young woman’s objectification…it remains the most evocative cinematic portrait of neocolonism.’9

It is Diouana’s inability to speak French, her ‘illiteracy’, that ultimately reclaims her from the invisibility borne of the incivility she experiences. ‘Language is one of the major ways that a culture is perpetuated…’10 – an assimilation policy that colonises the mind. According to Ngugi, “…cultural imperialism annihilates a people’s belief in their names, their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves…”11 She receives a letter from her mother, which she cannot read as it is written in French. It is read to her by Monsieur. What she hears is foreign to her. The language used is not her mother’s. She rejects this imposter, and the language that holds her captive and the culture that once captivated her, by tearing the letter to pieces. We hear her say, “I’m a prisoner here”, but as she removes herself from the room Monsieur as he writes ‘her’ response to her ‘mother’, the performance of decolonisation begins. Ras Michael & The Sons of Negus echo this renascence in their song ‘Mr. Brown’: “I hate Mr. Brown, I hate Mr. Brown…I am Ethiopian…How can a black man name Mr. Brown…All black man Ethiopian…No more slave man…”12

In 1966 Senegal is independent of colonial occupation by France but the ‘Black Girl’ is still being exploited in order to exact the maximum economic benefit, depreciating her in all aspects. However, the time of servitude and acquiescence is over. As one of the luncheon guests risibly announces “…their independence has made them less natural…” Diouana’s refusal to eat turns to a refusal to work, then a sleeping protest, which finally turns into a self-imposed isolation. Eventually, discarding her pretty western clothes (which at one point simultaneously symbolise her aspirations of a life in France and act as a mode of self-identification and expression), and returning to traditional attire, Diouana eschews the ‘false expectations of young Africans as they meet European culture…’13 – she civilises the uncivilised.

Diouana finally ‘wakes up’ by taking a final sleep. Her suicide is a type of ultimate rejection of this shadow ‘code civil’. It may suggest that 20th century Senegambian ‘citizens’ are courting an illusion akin to that of their 19th century counterparts: ‘the inhabitants of the quatre communes forged their own civilité which enabled them to participate in a global colonial culture on the basis of local idioms.’14 It is arguable whether their hybridised civil code – a form of resistance to a programme of dispossession – had any substantive worth. It is clear though that Diouana’s civility has no currency. It cannot return her home, it cannot send money to her mother and it barely merits a by-line in the local Côte d’Azur newspaper. The paper tells of her passing in the now familiar perfunctory manner which ‘reveals yet again the French’s indifference to the African’s condition…’15 – the French code of (in)civility.

“What will it take to drive the truth home

As the media manipulation overblows

The fact the fiction the tricks and tricknology

Years too late with their half-arsed apology

I got no acre and I got no mule

But I’m cool man, I know what I got to do

I’m gonna put a few things together

A construct of that thorn in the side

I’m gonna put a few things together

That’s a spanner in the works of a devil’s design

We don’t go no trust for dem

It’s just big bad word and cuss for dem

Do 4 self, move yourself

Man a stay true to self (we do)”16

I look forward to your musical responses to this mixtape. Click here for a full track listing

END

*The terms originaire and habitant are equivalent. They describe the status of the residents in the cities of Saint-Louis, Gorée, Rufisque and Dakar when they obtained the status of fully empowered communes and their habitants acquired citizenship. They also establish and make clear a difference between the originaires and the metropolitans with whom they live, and the Senegambians (the natives), their neighbours, subject to autochthonous powers before their conquest, then integrated into the colonial arena as subjects.

**Thus the identities that they produce is part of the story of colonisation and the religious, political and economic pattern of the French colonial empire, while at the same time borrowing elements from an autochthony revised by colonial contact. It is in this perspective that one must understand the central idea in the originaires’ struggle: special status. At the same time that they were pro-claiming allegiance to a French citizenship on which were based their rights, duties and individual pursuit of wealth and the defence of their commercial interests, they buttressed themselves with a culture all their own – they were not French culturally, but they were French politically and economically.

***`the most intelligent of the Blacks, the closest to the Europeans’ (Boilat, 1984: 5), a group generally referred to as gourmets (Catholic Black)

References

1, 4, 6, 8, 13, The French Colonial Policy of Assimilation and the Civility of the Originaires of the Four Communes (Senegal): A Nineteenth Century Globalization Project – Mamadou Diouf (Development and Change Vol.29 (1998) 671-696 ©Institute of Social Studies 1998. Published by Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 108 Cowley Rd, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK; pg. 674, 674, 675, 680, 675)

2, Wake Up – Brand Nubian from the album One for All (Elektra, #7559-60946-1, US, 1990)

3, 14, 15, Politics and style in Black Girl – Marsha Landy (from Jump Cut, no. 27, July 1982, pp.23-25; copyright Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 1982, 2005, pg. 2, 7, 10)

5, 10, From Imperialism to Diplomacy: A Historical Analysis of French and Senegal Cultural Relationship – Aisha Balarabe Bawa, Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto (pg. 2, 5)

7, Thieves in the night – Mos Def & Talib Kweli are Black Star from the album Mos Def & Talib Kweli are Black Star (Rawkus, #RWK 1158-1, US, 1998)

9, Film Review: Black Girl – Maria Garcia (Film Journal International, 17th May 2016 – http://www.filmjournal.com/reviews/film-review-black-girl )

11, Ngugi Wa Thion‟o, “Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature” Nairobi, East African Educational Publishers ltd.1981.

12, Mr. Brown – Ras Michael & The Sons of Negus from the album Rastafari (Grounation, GROL 505, UK, 1975)

16, Do 4 Self – Roots Manuva from the album Slime & Reason (Big Dada Recordings, BD123, UK, 2008)

Bibliography

- The French Colonial Policy of Assimilation and the Civility of the Originaires of the Four Communes (Senegal): A Nineteenth Century Globalization Project – Mamadou Diouf (Development and Change Vol.29 (1998) 671-696 ©Institute of Social Studies 1998. Published by Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 108 Cowley Rd, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK)

- Wake Up – Brand Nubian from the album One for All (Elektra, #7559-60946-1, US, 1990)

- Politics and style in Black Girl – Marsha Landy (from Jump Cut, no. 27, July 1982, pp.23-25; copyright Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 1982, 2005, pg. 2, 7, 10)

- From Imperialism to Diplomacy: A Historical Analysis of French and Senegal Cultural Relationship – Aisha Balarabe Bawa, Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto

- Thieves in the night – Mos Def & Talib Kweli are Black Star from the album Mos Def & Talib Kweli are Black Star (Rawkus, #RWK 1158-1, US, 1998)

- Black Girl: Lyrical Sympathy – Tony McKibbin (tonymckibbin.com – http://tonymckibbin.com/film/black-girl-2 )

- Introduction to Black Girl – Rahul Hamid (Senses of Cinema, December 2002, Cinematheque Annotations on Film, Issue 78)

- Ousmane Sembène’s “Black Girl” & African Storytelling Through Film – Hakeem Adam (Circumspecte, 27 January 2016, https://circumspecte.com/2016/01/ousmane-sembenes-black-girl-african-storytelling-through-film/)

- The “Black Girl” speaks, 1966 (Feminéma, posted by Didion, 20th March 2011- https://feminema.wordpress.com/category/films-by-name/black-girl-la-noire-de/ )

- Film Review: Black Girl – Maria Garcia (Film Journal International, 17th May 2016 – http://www.filmjournal.com/reviews/film-review-black-girl )

- Sembene Retrospective: Black Girl (1966) – K. A. Westphal (motion within motion, 7th October 2007 – http://motionwithinmotion.blogspot.co.uk/2007/10/sembene-retrospective-black-girl-1966.html )

- Black Girl: The Criterion Collection – Trevor Berrett (The Mooske and the Gripes, 24th January 2017 – http://mookseandgripes.com/reviews/2017/01/24/ousmane-sembene-black-girl/ )

- La Noire de… : Sembène’s Black Girl and Postcolonial Senegal – Sylvia Cutler (B.A. English 2017, http://humanities.byu.edu/la-noire-de-sembenes-black-girl-and-postcolonial-senegal/)

- Black Girl review – Ousmane Sembène’s groundbreaking film dazzles 50 years on – Jordan Hoffman (The Guardian, 18th Wednesday 2016 – https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/may/18/black-girl-review-ousmene-sembene-groundbreaking )

- Ousmane Sembène: Interview with Bonnie Greer (The Guardian, 5th June 2005 – https://www.theguardian.com/film/2005/jun/05/features )

- Black Girl Introduction and Post-Screening Q&A, Walker Art Center (https://youtu.be/VCoD7FDPbgY) – Published 16th February 2011, Post screening discussion at the Walker Art Center led by Charles Sugnet, Associate Professor, English Department, University of Minnesota, as part of the film series Ousmane Sembene: African Stories

- “Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature” Ngugi Wa Thion’o, (Nairobi, East African Educational Publishers ltd.1981)

- Do 4 Self – Roots Manuva from the album Slime & Reason (Big Dada Recordings, BD123, UK, 2008)

- Interview: Mbissine Thérèse Diop – Livia Bloom (Film Comment, published 5th October 2015, https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/interview-mbissine-therese-diop/)